Differences between Obamacare and Romneycare

Obamacare vs. Romneycare

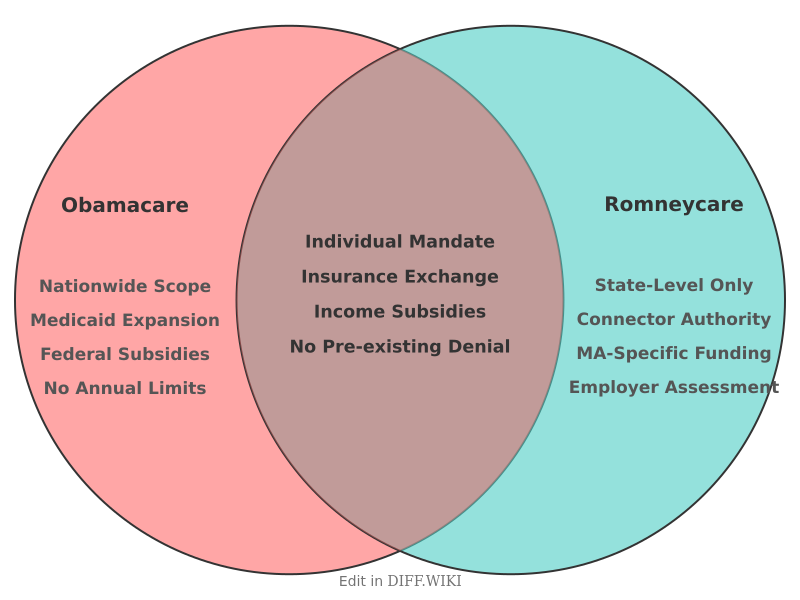

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), commonly known as Obamacare, and the Massachusetts health care reform law of 2006, often called Romneycare, share foundational principles but differ in their scale, scope, and specific provisions. The Massachusetts law, enacted under then-Governor Mitt Romney, served as a key model for the nationwide ACA passed in 2010.[1][2] Both initiatives aimed to increase health insurance coverage through a combination of individual mandates, employer requirements, and subsidized insurance marketplaces.[3][4]

The core of both laws was the "individual mandate," which required most residents to obtain health insurance or pay a penalty.[5] This approach was designed to ensure a broad insurance pool that included healthy individuals, which helps to offset the costs of covering those with greater medical needs.[3] Both reforms also established health insurance exchanges where individuals could compare and purchase private insurance plans, often with financial assistance.[2] Additionally, they both expanded eligibility for Medicaid to cover more low-income residents and prohibited insurance companies from denying coverage due to pre-existing conditions.[3]

Despite these structural similarities, significant distinctions exist, primarily due to the ACA's national application compared to Romneycare's state-level implementation.[2] The ACA addressed a much larger and more diverse population, leading to different funding mechanisms and regulatory details.[2]

Comparison Table

| Category | Obamacare (Affordable Care Act) | Romneycare (Massachusetts Health Reform) |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | National program covering all 50 states and over 300 million people.[2] | State-level program for the 6.5 million residents of Massachusetts.[2] |

| Individual Mandate Penalty | The penalty for not having insurance was a set dollar amount or a percentage of income, whichever was higher. The federal penalty was later reduced to zero. | The penalty was calculated based on 50 percent of the cost of the lowest-priced insurance plan available through the state's exchange. |

| Employer Mandate | Required businesses with 50 or more full-time employees to offer insurance or pay a penalty of $2,000 per employee (with an exemption for the first 30).[2][3] | Required businesses with 11 or more employees to provide health benefits or pay a $295 per-employee "Fair Share" contribution.[2] This was later repealed in favor of the federal mandate. |

| Subsidies | Provides subsidies for individuals and families with incomes up to 400% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL).[2] | Initially provided subsidies for those with incomes up to 300% of the FPL.[2][3] |

| Financing | Funded through a combination of taxes, including new levies on medical devices and high-income earners. | Primarily funded through federal Medicaid payments and redirecting existing state funds for uncompensated care. |

| Preventive Services | Mandated that insurance policies cover a range of preventive services with no co-pays or deductibles.[2] | Allowed insurers to require co-pays for some preventive services.[2] |

| Dependent Coverage | Allows young adults to remain on their parents' insurance plans until age 26. | Allowed young adults to remain on their parents' plans up to age 25. |

One of the most noted differences was the source of funding. While Massachusetts was able to leverage federal Medicaid dollars to help finance its reform, the ACA required new revenue streams at the national level. The ACA also included a broader range of provisions beyond insurance coverage, such as measures to address healthcare provider shortages and promote wellness programs.[2] The subsidy structures also varied, with the ACA extending financial assistance to individuals and families at higher income levels than the initial Massachusetts law.[2] The requirements for employers were also distinct, with different thresholds for company size and penalty amounts.

References

- ↑ "mahealthconnector.org". Retrieved January 19, 2026.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 "cbsnews.com". Retrieved January 19, 2026.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "americanprogress.org". Retrieved January 19, 2026.

- ↑ "nih.gov". Retrieved January 19, 2026.

- ↑ "ucsb.edu". Retrieved January 19, 2026.