Differences between Catholicism and Zen

Catholicism vs. Zen

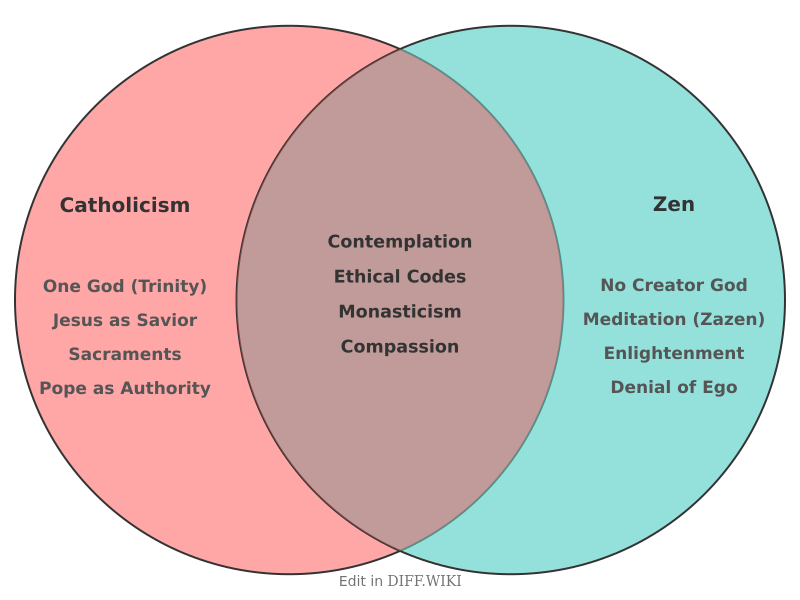

Catholicism and Zen are belief systems with fundamentally different origins, theological foundations, and ultimate goals. Catholicism is a monotheistic Abrahamic religion centered on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as presented in the New Testament.[1][2] Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism that originated in China and emphasizes meditation and direct insight into the nature of reality.[3][4] While both traditions have contemplative practices and value a form of self-diminishment, their core doctrines are distinct.[5]

The Catholic worldview is grounded in the belief in one God, a Trinity of three co-equal persons: the Father, the Son (Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit. This God is understood as the creator of heaven and earth. The central goal for a Catholic is salvation from sin and eternal union with God, achieved through faith in Jesus Christ and participation in the Church's sacraments.[2]

In contrast, Zen does not focus on a creator God. Its philosophical foundation rests on concepts such as emptiness (śūnyatā) and the absence of a permanent, independent self (anātman). The[3] ultimate aim in Zen is to achieve enlightenment (satori), which is a direct experiential insight into one's own Buddha-nature and the nature of reality. This is pursued primarily through the practice of seated meditation, known as zazen.

Comparison Table

| Category | Catholicism | Zen |

|---|---|---|

| Ultimate Reality | One creator God existing as a Trinity (Father, Son, Holy Spirit). | The[1] concept of a creator God is absent. Reality is characterized by emptiness (śūnyatā) and dependent origination. |

| [3]Ultimate Goal | Salvation from sin and eternal union with God in heaven. | To attain enlightenment (satori) and experience the true nature of reality, ending the cycle of suffering. |

| View of the Self | A unique, individual soul created by God, which is immortal. | The concept of a permanent, individual self (ātman) is seen as an illusion. The doctrine of anātman (no-self) is central. |

| Primary[3] Practice | Prayer, participation in sacraments (like the Eucharist), and acts of faith and charity. | Seated meditation (zazen) to calm the mind and allow for direct insight. |

| Role[4] of Scripture | The Bible is considered the inspired, authoritative Word of God, central to faith and doctrine. | While it has its own body of texts, Zen de-emphasizes reliance on scripture, favoring direct experience over doctrine. |

| Key[4] Figure(s) | Jesus Christ, considered the Son of God and savior. | Siddhartha[2] Gautama (the Buddha), and subsequent patriarchs like Bodhidharma. |

| Clergy[4] | A celibate, male priesthood (priests, bishops) with the authority to administer sacraments. | Teachers or masters (Rōshi) guide students. Priests exist, but in many Japanese traditions, they may marry. |

| View of Suffering | Can be redemptive, a way to unite one's suffering with that of Christ for salvific purposes. | Arises from attachment, craving, and ignorance; the goal is to eliminate its root causes. |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "dioceseoflansing.org". Retrieved January 25, 2026.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "npcat.org.uk". Retrieved January 25, 2026.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "mai-ko.com". Retrieved January 25, 2026.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "ngv.vic.gov.au". Retrieved January 25, 2026.

- ↑ "lionsroar.com". Retrieved January 25, 2026.