Differences between AAC and MP3

Contents

AAC vs. MP3[edit]

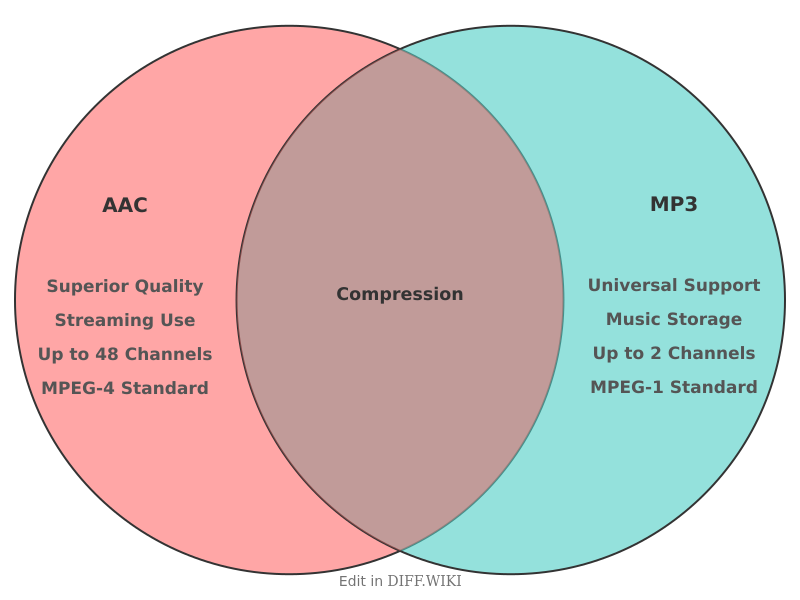

Advanced Audio Coding (AAC) and MPEG-1 Audio Layer III (MP3) are both digital audio encoding formats that use lossy compression.[1] This process reduces audio file sizes by selectively discarding some sound data.[2] MP3 became the de facto standard for digital music in the late 1990s, popular for its ability to make audio files small enough for internet transfer and storage on portable devices.[3][4] AAC was developed later as a successor to MP3, designed to provide better sound quality at similar bitrates.[5]

While both formats serve a similar purpose, AAC generally offers more efficient compression and better audio quality than MP3, particularly at lower bitrates. For instance, a 128 kbps AAC file is often perceived as having clearer sound than an MP3 of the same bitrate, which can sometimes sound indistinct. The difference in quality becomes less noticeable at higher bitrates, such as 256 kbps or 320 kbps.

AAC's adoption has been widespread, becoming the standard format for platforms like Apple's iTunes, YouTube, and various streaming services. MP3, however, maintains universal compatibility with nearly all digital audio devices and software due to its longer history.

Comparison Table[edit]

| Category | Advanced Audio Coding (AAC) | MPEG-1 Audio Layer III (MP3) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Streaming, digital music downloads, broadcasting[1] | Digital music storage and playback[3] |

| Compression Efficiency | Higher; generally better sound quality at the same bitrate | Lower; quality can degrade noticeably at lower bitrates |

| Sound Quality | Often perceived as superior, especially below 192 kbps | Good quality at higher bitrates, but can be less clear at lower settings |

| Device Compatibility | Wide support on modern devices, standard for Apple products | Universal support across nearly all devices and software |

| Channel Support | Up to 48 channels, suitable for surround sound | Up to two channels in its original specification, with later extensions for 5.1 |

| Sample Frequencies | 8 kHz to 96 kHz | 16 kHz to 48 kHz |

| Standardization | Part of MPEG-2 and MPEG-4 standards | Part of the MPEG-1 and MPEG-2 standards[2] |

History and Development[edit]

Development of the MP3 format began in the late 1980s at the Fraunhofer Institute in Germany as part of the MPEG-1 standard.[3][4] It became widely available in the mid-1990s, and its popularity grew with the rise of the internet and file-sharing applications like Napster.[2] The release of the Winamp media player in 1997 and Apple's iPod in 2001 further solidified MP3's dominance.[2]

AAC was developed in the early to mid-1990s by a consortium of companies including Fraunhofer IIS, AT&T Bell Laboratories, Dolby, and Sony. It was standardized in 1997 as part of the MPEG-2 standard and later incorporated into the MPEG-4 standard. The format was designed to be a more efficient successor to MP3.[5] Apple's adoption of AAC for the iTunes Store and iPods in 2003 was a key factor in its growth.

Technical Differences[edit]

AAC employs more advanced and efficient encoding algorithms than MP3. It uses a pure Modified Discrete Cosine Transform (MDCT), which improves compression efficiency.[5] AAC also features a wider range of sample frequencies (from 8 kHz to 96 kHz) compared to MP3 (16 kHz to 48 kHz), and supports up to 48 audio channels, making it more suitable for multi-channel and high-resolution audio.

MP3, on the other hand, uses a hybrid coding algorithm.[5] While effective for its time, its technology is less efficient than that of AAC, especially at lower data rates. This can lead to audible compression artifacts, often described as a "muddy" or "slurry" sound, in MP3 files encoded at 128 kbps or lower.

Licensing[edit]

For many years, the use of MP3 encoders required licensing fees paid to the patent holders. However, the patents related to the MP3 format have expired, with the primary licensing program ending in 2017, making it free to use. AAC is not royalty-free; its use in hardware or software requires licenses from patent holders, though the cost is generally handled by the manufacturer and is not a direct charge to the consumer.

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "cloudinary.com". Retrieved December 30, 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "freesheetmusic.net". Retrieved December 30, 2025.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "alm.com". Retrieved December 30, 2025.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "applesinstereo.com". Retrieved December 30, 2025.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "wikipedia.org". Retrieved December 30, 2025.