Differences between Frederick Griffith and Oswald Avery

Contents

Frederick Griffith vs. Oswald Avery[edit]

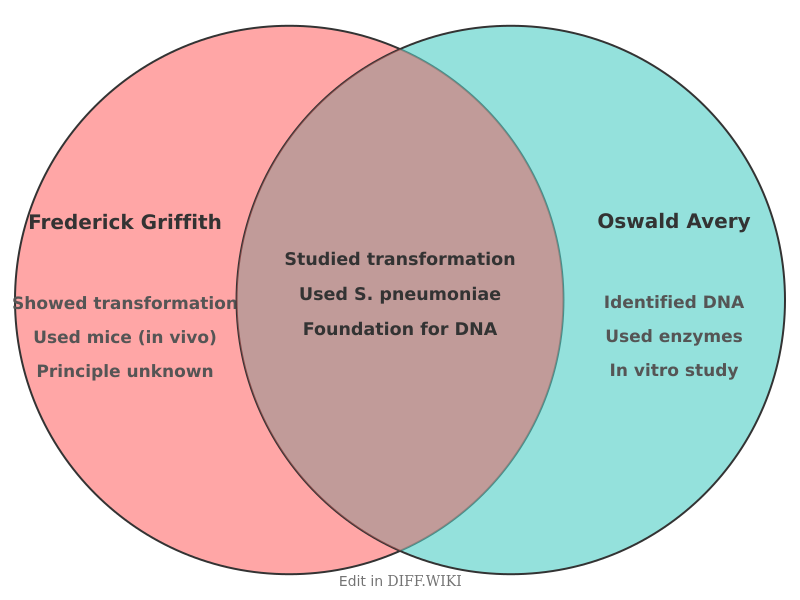

The work of Frederick Griffith and Oswald Avery was foundational in identifying DNA as the carrier of genetic information. Griffith's 1928 experiment revealed a "transforming principle" that could alter bacteria, while Avery's subsequent research, published in 1944, chemically identified this principle as DNA.[1][2] Though Avery's work was a direct extension of Griffith's, their experiments, conclusions, and the nature of their evidence differed significantly. At the time of their research, most scientists believed that proteins, due to their complexity, held the key to heredity.[3]

Comparison Table[edit]

| Category | Frederick Griffith | Oswald Avery |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Investigation | Demonstrated that a "transforming principle" could be transferred between bacteria.[4] | Chemically identified the "transforming principle" as DNA.[2] |

| Organism Used | Streptococcus pneumoniae strains in mice (in vivo).[1] | Purified components from Streptococcus pneumoniae in test tubes (in vitro). |

| Key Observation | A mixture of heat-killed virulent bacteria and live non-virulent bacteria was lethal to mice, from which live virulent bacteria were recovered.[5] | Transformation of non-virulent bacteria was prevented only when the extract from heat-killed virulent bacteria was treated with an enzyme that destroys DNA (DNase). |

| Nature of Evidence | Indirect, based on the observed change in the bacteria's physical form and virulence within a living host. | Direct, biochemical evidence based on the systematic elimination of other molecular candidates like protein and RNA. |

| Main Conclusion | An unknown, heritable substance is capable of transforming bacteria from one type to another.[1] | DNA is the substance responsible for heredity and the transformation of bacteria. |

| Scientific Impact | Established the phenomenon of bacterial transformation, opening a new line of genetic inquiry. | Provided the first major experimental proof that DNA is the genetic material, laying the groundwork for molecular genetics. |

Griffith's Experiment[edit]

In 1928, British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith was studying two strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae: a virulent "smooth" (S) strain with a protective polysaccharide capsule, and a non-virulent "rough" (R) strain without one.[5] He observed that mice injected with the live S strain died, while those injected with the live R strain or heat-killed S strain survived. Critically, when he injected mice with a mixture of heat-killed S strain and live R strain, the mice died.[2] From the dead mice, Griffith isolated live S strain bacteria. He concluded that some "transforming principle" from the dead S strain had been transferred to the R strain, enabling it to create a smooth capsule and become virulent.[5] However, the chemical nature of this principle remained unknown.[4]

Avery–MacLeod–McCarty Experiment[edit]

Building on Griffith's discovery, Oswald Avery and his colleagues Colin MacLeod and Maclyn McCarty worked for over a decade at the Rockefeller Institute to identify the transforming principle. In their 1944 paper, they described how they prepared an extract from heat-killed S strain bacteria and systematically used enzymes to eliminate different classes of molecules. They[3] found that treating the extract with proteases (which destroy protein) or ribonuclease (which destroys RNA) did not stop the transformation of R strain bacteria into S strain. Only[2] when they treated the extract with deoxyribonuclease (DNase), an enzyme that breaks down DNA, did the transformation fail to occur. This experiment provided clear evidence that DNA was the transforming principle and the molecule of heredity, a conclusion that was initially met with skepticism but eventually became a cornerstone of biology.

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "wikipedia.org". Retrieved January 16, 2026.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "genome.gov". Retrieved January 16, 2026.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "biopathogenix.com". Retrieved January 16, 2026.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "study.com". Retrieved January 16, 2026.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "study.com". Retrieved January 16, 2026.