Differences between Judaism and Zoroastrianism

Contents

Judaism vs. Zoroastrianism[edit]

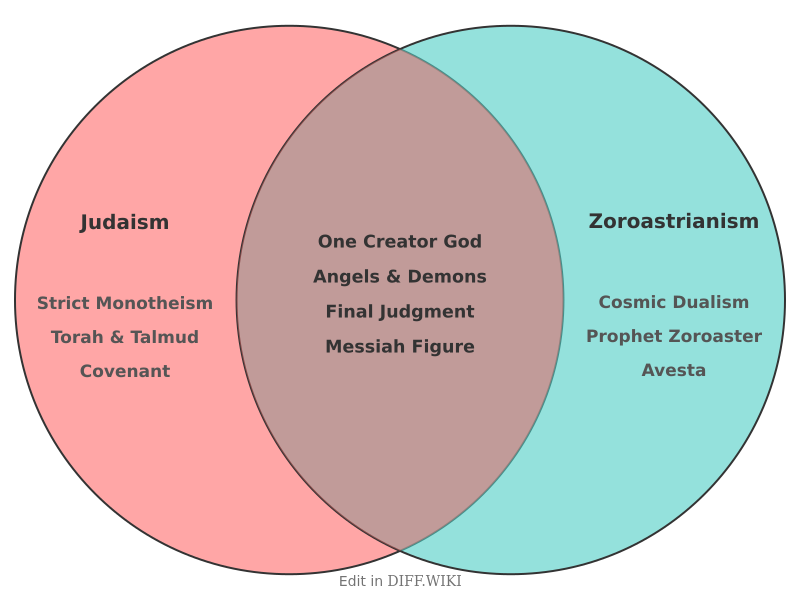

Judaism and Zoroastrianism are two of the world's oldest monotheistic religions, with Zoroastrianism likely predating Judaism's shift to monotheism.[1] Originating in ancient Persia, Zoroastrianism was founded by the prophet Zoroaster (or Zarathustra).[2][3] Judaism began with the patriarch Abraham in the Levant.[4] The Babylonian Exile of the Jews in the sixth century BCE led to significant contact with the Persian Empire, a period where scholars believe Zoroastrian concepts influenced Jewish theology, particularly in areas like eschatology, angelology, and demonology.[2][5]

While both faiths are revealed religions centered on a single creator god, their core theological frameworks differ.[2] Judaism is strictly monotheistic, asserting that one God is the source of everything, including both good and evil. In contrast, Zoroastrianism is often characterized as dualistic, positing a cosmic struggle between the supreme and good creator, Ahura Mazda, and an opposing, evil spirit known as Angra Mainyu or Ahriman.[5]

Ideas such as a final judgment, the resurrection of the dead, and a messianic savior figure are prominent in both traditions.[2][5] The Jewish concept of the Messiah is seen by many scholars as having been influenced by the Zoroastrian figure of the Saoshyant, a benefactor who leads humanity in the final renovation of the world.

Comparison Table[edit]

| Category | Judaism | Zoroastrianism |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Levant, circa 4,000 years ago with Abraham.[1] | Ancient Persia (modern Iran), founded by the Prophet Zoroaster, dated as early as 3,500 years ago.[2] |

| Deity | Adherence to strict monotheism; God (Yahweh) is the sole creator and source of both good and evil. | Fundamentally monotheistic but with a dualistic cosmology; Ahura Mazda is the one supreme God, but his creation is opposed by an evil spirit, Angra Mainyu.[5] |

| Main Prophet | Moses, who received the Torah on Mount Sinai.[2] | Zoroaster (Zarathustra), who received the revelation from Ahura Mazda.[2] |

| Primary Texts | The Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), especially the first five books known as the Torah. The Talmud is the primary source of oral law.[4] | The Avesta, the oldest parts of which are the Gathas, hymns believed to have been composed by Zoroaster.[2] |

| View on Evil | Evil is not an independent force but represents an opposition to God's will or a deprivation of good. God is the ultimate creator of both "light and darkness." | Evil is an independent and opposing force to good, represented by the spirit Angra Mainyu in a cosmic struggle against Ahura Mazda.[5] |

| Messianic Figure | The Messiah, an "anointed one" who will bring about a messianic era. | The Saoshyant, a savior figure who brings about the final renovation of the world (Frashokereti). |

| Afterlife | Early texts describe a shadowy existence in Sheol, but later thought, influenced by Zoroastrianism, developed concepts of resurrection, a final judgment, and Heaven (Olam Ha-Ba) and Hell (Gehinnom).[5] | Belief in a final judgment where the soul is judged after death, followed by a resurrection of the dead and the ultimate triumph of good.[5][2] |

Alleged Influence on Judaism[edit]

The period of the Babylonian Exile and the subsequent rule of the Persian Achaemenid Empire is a focal point for understanding the relationship between the two religions. During this time, Jewish thinkers were exposed to Zoroastrian ideas.[5] Many scholars argue that core Zoroastrian eschatological concepts—such as a final judgment, the bodily resurrection of the dead, and a detailed angelology and demonology—became more pronounced in Jewish thought during and after this period.

Before[2][5] this contact, the Hebrew Bible's depiction of the afterlife was more ambiguous, often referencing a shadowy realm called Sheol. Later[5] texts, like the Book of Daniel, contain more explicit references to resurrection and judgment, concepts that are central to Zoroastrianism. Similarly,[5] the personification of an adversary figure (Satan) in Judaism evolved from a servant of God to a more independent, evil entity, a development some scholars attribute to the influence of the Zoroastrian figure Ahriman. The Jewish messianic hope is also believed by some to have been shaped by the Zoroastrian prophecy of the Saoshyant. However, other scholars maintain that these Jewish beliefs evolved independently or that the influence was reciprocal.[2]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "quora.com". Retrieved December 27, 2025.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 "quora.com". Retrieved December 27, 2025.

- ↑ "jewishencyclopedia.com". Retrieved December 27, 2025.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "difference.wiki". Retrieved December 27, 2025.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 "quora.com". Retrieved December 27, 2025.