Differences between Mahayana and Theravada

Contents

Mahayana vs. Theravada[edit]

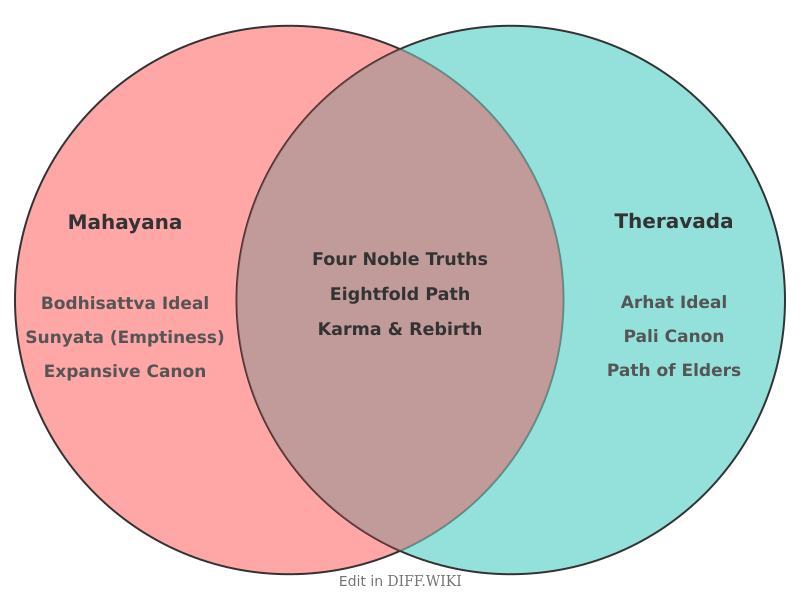

Buddhism is principally divided into two major branches: Theravada and Mahayana. Theravada, meaning "The School of the Elders," is the older and more conservative of the two schools.[1][2] It is the dominant form of Buddhism in countries such as Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.[2] Mahayana, which means "The Great Vehicle," emerged several centuries after the Buddha's death and is predominant in North and East Asia, including China, Japan, Korea, and Tibet.[1] While both schools share core teachings derived from the historical Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, they differ in their scriptural canons, ultimate goals, and understanding of the Buddha's nature.[3]

Comparison Table[edit]

| Category | Theravada | Mahayana |

|---|---|---|

| Ultimate Goal | Attainment of Arhatship (personal liberation from the cycle of rebirth, samsara).[1] | Attainment of Buddhahood via the Bodhisattva path, for the liberation of all sentient beings. |

| Key Figure | The Arhat, a "perfected person" who has achieved nirvana by following the Buddha's teachings.[4][5] | The Bodhisattva, an enlightened being who postpones their own final nirvana out of compassion to help others achieve it. |

| View of the Buddha | Siddhartha Gautama is seen as the historical Buddha, a supreme teacher who showed the path to enlightenment but is no longer active in the world. | The historical Buddha is one of many manifestations. The concept of Trikaya ("three bodies") presents the Buddha as having an ultimate, celestial, and physical form. |

| Scriptural Canon | The Pali Canon (Tipitaka) is considered the most authoritative collection of the Buddha's original teachings.[2] | In addition to the early scriptures (Agamas), accepts a broader canon of later texts, known as Mahayana Sutras. |

| Concept of Emptiness | Focuses on Anatta (not-self), the doctrine that there is no permanent, underlying self in living beings.[1] | Expands on Anatta with the concept of Shunyata (emptiness), stating that all phenomena are without intrinsic existence or independent identity.[1] |

| Pantheon | Recognizes the historical Buddha and past buddhas. Devotion is primarily directed toward the Buddha as an exemplary teacher.[1] | Includes a vast pantheon of Buddhas (like Amitābha) and Bodhisattvas (like Avalokiteshvara) who are objects of devotion and can offer assistance to practitioners. |

The Ideal Practitioner: Arhat and Bodhisattva[edit]

A central distinction between the two branches is the ideal practitioner. In Theravada, the goal is to become an Arhat, an individual who has attained full enlightenment and liberation from samsara by diligently following the path laid out by the Buddha. This path is viewed as a personal journey requiring individual effort, with monastic life considered the most direct route. [1] Mahayana Buddhism introduces the ideal of the Bodhisattva. A Bodhisattva is a being who has generated a profound desire to achieve Buddhahood for the sake of all other beings. Motivated by great compassion, they postpone their own entry into final nirvana to remain in the cycle of rebirth and guide others toward enlightenment. This path is presented as being available to all practitioners, not only monastics.

Scripture and the Nature of the Buddha[edit]

Theravada adheres strictly to the Pali Canon, a collection of scriptures believed to contain the earliest recorded teachings of the Buddha. Later[2] texts, such as the Mahayana sutras, are generally not considered authentic words of the Buddha. [2] Mahayana accepts the early scriptures (known in their canon as the Agamas) but also incorporates a vast body of later sutras, such as the Lotus Sutra and Heart Sutra. These texts are believed to reveal deeper, more advanced doctrines that the Buddha taught to specific disciples. Mahayana philosophy also developed the Trikaya doctrine, which describes the Buddha as having three "bodies": an ultimate transcendent body (Dharmakaya), a celestial body of bliss (Sambhogakaya), and an earthly manifestation body (Nirmanakaya). This contrasts with the Theravada view, which focuses on the historical, human teacher Siddhartha Gautama.

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "hdasianart.com". Retrieved December 20, 2025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "wikipedia.org". Retrieved December 20, 2025.

- ↑ "wikipedia.org". Retrieved December 20, 2025.

- ↑ "mindvalley.com". Retrieved December 20, 2025.

- ↑ "hdasianart.com". Retrieved December 20, 2025.